Mataupu

Insttitial cystitis (tigā tigā syndrome)

Interstitial cystitis: what is it?

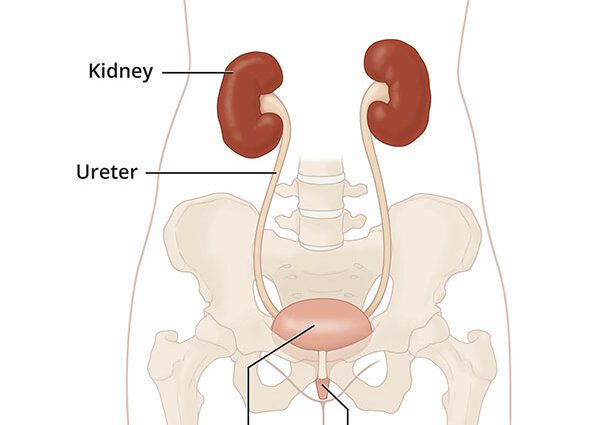

La interstitial cystitis o se bladder disease rare but disabling which has changed its name. It is now called painful bladder syndrome. It is characterized by pain in the lower abdomen and uunai soo e urination, day and night. These pains and these urges to urinate are often very intense, sometimes unbearable, to the point that interstitial cystitis can constitute a real social handicap, preventing people from leaving their homes. The pain can also affect the urethra (the channel that carries urine from the bladder to the outside) and, in women, the vagina (see diagram). Urinating (the urination) partially or completely relieves these pains. Interstitial cystitis affects especially women. It can be declared at any age from 18 years old. At the moment, there is no cure for this condition, which is considered to be taimi masani.

Be careful not to confuse interstitial cystitis et cystitis : “classic” cystitis is a urinary tract infection caused by bacteria; interstitial cystitis is not not an infection and its cause is not known.

Manatua. I le 2002, o leInternational Continence Sosaiete (ICS), published recommendations suggesting the use of the term ” interstitial cystitis-painful bladder syndrome Rather than that of interstitial cystitis alone. In fact, interstitial cystitis is one of the painful bladder syndromes, but there are special features visible on examination in the bladder wall. |

Faʻaauau

According to the Interstitial Cystitis Association of Quebec, approximately 150 Canadians are affected by this disease. It seems that the interstitial cystitis is less frequent in Europe than in North America. However, it is difficult to get an accurate estimate of the number of people affected, as the disease is underdiagnosed. It is estimated that there are between 1 and 7 people with interstitial cystitis per 10 people in Europe. In the United States, this more frequent disease affects one in 000 people.

Interstitial cystitis affects about 5 to 10 times more women than men. It is usually diagnosed around the age of 30 to 40, and 25% of those affected are under 30.

Mafuaaga

In interstitial cystitis, the inner wall of the bladder is the site of visible inflammatory abnormalities. Small sores on this wall on the inside of the bladder can leak a little blood and cause pain and the urge to empty the bladder of acidic urine.

The origin of the inflammation observed in the interstitial cystitis is not known for sure. Some people link its onset to surgery, childbirth, or a serious bladder infection, but in many cases it seems to occur without a trigger. Interstitial cystitis is probably a multifactorial disease, involving several causes.

tele manatu sese are under consideration. Researchers evoke those of an allergic reaction, a reaction autoimmune or a neurological problem in the wall of the bladder. It is not excluded that hereditary factors also contribute to it.

Here are the tracks most often mentioned:

- Alteration of the bladder wall. For some reason, the protective layer lining the inside of the bladder (cells and proteins) is impaired in many people with interstitial cystitis. This layer normally prevents irritants in urine from coming into direct contact with the bladder wall.

- Less effective intravesical protective layer. In people with interstitial cystitis, this protective layer would work less effectively. Urine could therefore irritate the bladder and cause inflammation and a burning sensation, such as when alcohol is applied to a wound.

- A substance called AFP or antiproliferative factor is found in the urine of people with interstitial cystitis. It may be to blame, because it seems to inhibit the natural and regular renewal of cells lining the inside of the bladder.

- Maʻi faʻamaʻi. Inflammation of the bladder could be caused by the presence of harmful antibodies against the wall of the bladder (autoimmune reaction). Such antibodies have been found in some people with interstitial cystitis, without it being known whether they are the cause or the consequence of the disease.

- Hypersensitivity of the nerves in the bladder. The pain experienced by people with interstitial cystitis could be “neuropathic” pain, that is, pain caused by dysfunction of the nervous system of the bladder. Thus, a very small amount of urine would be enough to “excite” the nerves and trigger pain signals rather than just a feeling of pressure.

talutalu

The syndrome progresses differently from person to person. At the beginning, the faailoga tend to appear and then disappear on their own. The periods of faʻamagaloga can last for several months. The symptoms tend to get worse over the years. In this case, the pain increases and the urge to urinate becomes more frequent.

In the most severe cases, the manaʻomia urosa can occur up to 60 times in 24 hours. Personal and social life is greatly affected. The pain is sometimes so intense that discouragement and frustration can lead some people to depression, and even to depression. tōaʻi. Support from loved ones is of crucial importance.

Diagnostic

According to the Mayo Clinic in the United States, people with interstitial cystitis receive their diagnosis on average 4 years after the onset of the disease. In France, a study conducted in 2009 showed that the diagnostic delay was even longer and corresponded to 7,5 years21. This is not surprising since interstitial cystitis can easily be confused with other health problems: urinary tract infection, endometriosis, chlamydial infection, kidney disease, an “overactive” bladder, etc.

Le faʻautaga maʻi is difficult to establish and can only be confirmed after all other possible causes have been ruled out. Moreover, it is an affection again poorly known doctors. It still happens that it is qualified as a “psychological problem” or imaginary by several doctors before the diagnosis is made, while the interior aspect of the inflammatory bladder is very telling.

Here are the most common tests done to diagnose interstitial cystitis:

- Urinalysis Culture and analysis of a urine sample can determine if there is a UTI. When it comes to interstitial cystitis, there are no microbes, the urine is sterile. But there can be blood in the urine (hematuria) sometimes even very little (microscopic hematuria in which case we see red blood cells under the microscope, but no blood with the naked eye). With interstitial cystitis, white blood cells can also be found in the urine.

- Cystoskopi with hydrodistension of the bladder. This is a test to look at the wall of the bladder. This examination is performed under general anesthesia. The bladder is first filled with water so that the wall is distended. Then, a catheter with a camera is inserted into the urethra. The doctor inspects the mucosa by viewing it on a screen. He looks for the presence of fine cracks or small hemorrhages. Called glomerulations, these small bleeds are very characteristic of interstitial cystitis and present in 95% of cases. In some less common cases, there are even typical sores called O papala a Hunner. Sometimes the doctor will do a biopsy. The removed tissue is then observed under a microscope for further evaluation.

- The urodynamic assessment comprising udo cystometry and urodynamic examination can also be carried out, but these examinations are less and less practiced, because they are not very specific and therefore not very useful and often painful. In case of interstitial cystitis, we discover with these examinations that the volumetric capacity of the bladder is reduced and that the desire to urinate and the pain appear for a lower volume than in a person not suffering from interstitial cystitis. These examinations nevertheless make it possible to detect hyperactivities of the bladder (overactive bladder) another functional disease also causing the urge to urinate.

- Potassium sensitivity test. Less and less practiced, because not very specific with 25% false negatives (the test suggests that the person does not have interstitial cystitis while in 25% of cases it is!) And 4% false positive (the test suggests that the person has interstitial cystitis when they do not).

Using a catheter inserted into the urethra, the bladder is filled with water. Then, it is emptied and filled with a potassium chloride solution. (Lidocaine gel is first applied around the opening of the urethra to reduce the pain of inserting the catheter.) On a scale of 0 to 5, the person indicates how urgent they feel to be. urinating and the intensity of the pain. If symptoms are increased when tested with the potassium chloride solution, it may be a sign of interstitial cystitis. Normally, no difference should be felt between this solution and the water.